“Polaris UT” and “#YCP” Joint Survey:

WHY DOES THE ENROLLMENT RATIO OF WOMEN STUDENTS REMAIN LOW AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TOKYO?

GREETINGS AND SUMMARY

The University of Tokyo continues to exhibit a gender distribution imbalance, with female students comprising a mere 20% of the total enrollment. Several theories have arisen to explain this phenomenon, such as the suggestion that young women are disinclined to face the challenges of academic uncertainty, colloquially referred to as becoming a ‘Ronin’. Concerns over additional financial cost and safety associated with female students’ independent living arrangement have been also posited. Nonetheless, substantiating evidence is notably absent, casting doubt on the accuracy of these conjectures as primary drivers of the prevailing gender disparity within the university's student body.

In an effort to uncover the underlying causal factors and gauge their impact on the underrepresentation of women within the University of Tokyo's undergraduate ranks, we have undertaken a nationwide survey which encompassed a cohort of 4,000 second-year high school students. By examining their aspirations, concerns, and constraints, our study seeks to shed light on the interplay of elements contributing to the limited female presence among the university's students.

Our findings regarding factors influencing the low representation of female

students at UTokyo include:

• The tendency of girls to underestimate their academic abilities.

• The general female aversion to taking a "ronin" year for exam preparation.

• Their preference for avoiding residence in Tokyo.

• Their inclination, especially outside the Greater Tokyo area, to not consider their educational accomplishment ("gakureki") as important for the future.

• Parents' attitudes toward daughters (compared to those toward sons), such as their tendency to discourage them from experiencing a "ronin" year and their lower expectations for studying at high-ranking universities.

At Polaris (UT), we are committed to leveraging the insights gained from this survey to enhance our initiatives. Our aim is to provide more effective support for women in junior and senior high schools as they navigate their career choices.

Makoto Tanaka

President

Polaris (UT) (with members consisting of undergraduate and graduate students

from the University of Tokyo)

Translators’ note: The modern definition of “ronin” is a student who has failed an (annual) college entrance exam and is studying to take it again. Originally, the term referred to a Samurai without a master.

OUTLINE OF SURVEY

Objective:

The primary objective of this survey is to discern the variations in the academic

environment and attitudes toward university enrollment between male and female

high school students. By undertaking this analysis, we aspire to shed light on the

underlying factors that contribute to the limited growth in the proportion of female

students at the University of Tokyo.

Samples:

Our survey encompasses a set of 97 high schools around Japan. These schools

were selected based on a specific criterion: a track record of producing five or

more successful applicants to the University of Tokyo annually over the past

several years. The participant pool consists of both male and female second-year

high school students who are currently enrolled in these select institutions and

have voluntarily participated in the survey. The total number of valid responses for

analysis stands at 3716 cases, maintaining a balanced male-to-female respondent

ratio of 1:1.

Data Collection Method:

The survey was administered using a Google Form platform, allowing for flexibility

and accessibility in the response collection process. Respondents were provided

with two options for participation: (a) electronically completing the Google Form

online or (b) manually filling out a printed version of the Google Form

questionnaire. In the latter case, the completed questionnaires were subsequently

postal mailed to Polaris (UT) and #YCP either by students themselves or school

administrators.

Survey Period:

The data collection period extended from February 7 to April 15, 2023. This

timeframe ensured comprehensive data capture and allowed participants sufficient

opportunity to contribute to the study.

Theme 1. Do Women Have a Tendency to Avoid the “Ronin” Experience?

◉ "Ronin" Avoidance Trend ◉

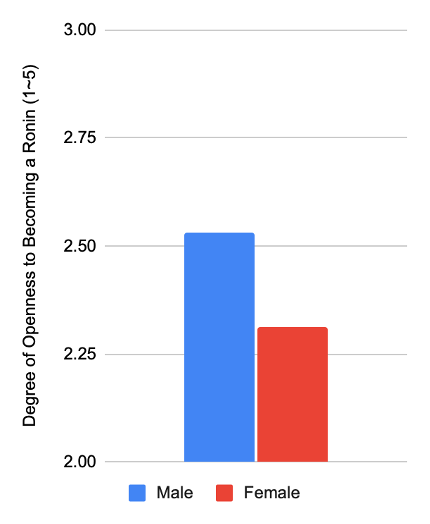

One of the frequently cited reasons for the low percentage of female students at UTokyo is the tendency of women to avoid the "ronin" experience. Indeed, this survey of second-year high school students also reveals that, in comparison to boys, girls have a propensity to steer clear of the "ronin" phenomenon, particularly outside the Greater Tokyo area (p < .001).

The proportion of females within the current "ronin" category is even lower than that among current high school students. Given that a significant segment of successful UTokyo applicants are "ronin," it is evident that this situation has contributed to an overall decrease in the female enrollment rate at the University of Tokyo.

P

Figure 1: The average degree of “openness to becoming a ronin” of male and female students.

◉ Relationship between "Degree of Openness to Becoming a Ronin" and "Desire to Attend the University of Tokyo" ◉

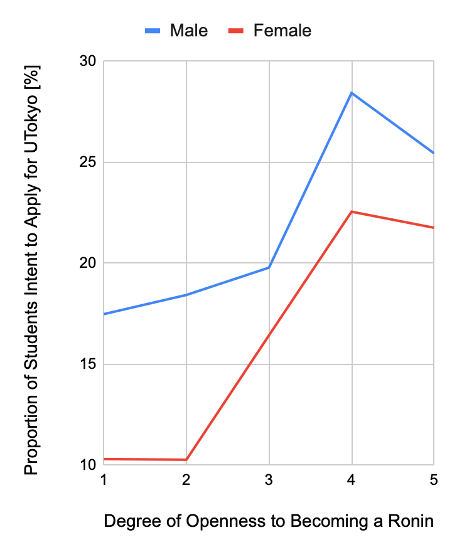

The survey reveals a positive correlation between the "degree of openness to becoming a ronin" and the "applicant's desire to apply to the University of Tokyo" among the surveyed students (refer to Footnote 1). Consequently, high school students who display reluctance towards adopting the "ronin" route tend to 1) opt for "safety" schools after failing to clear the UTokyo entrance exam, and 2) lower their targeted universities' standards during the early stages of entrance exam preparation (even before attempting the UTokyo entrance exam).

Figure 2: The relationship between “degree of openness to becoming a ronin” and the proportion of students who has the intention to apply for the University of Tokyo.

◉ Parental Influence ◉

The survey also demonstrates that the greater a student's parents object to their child becoming a "ronin," the more likely the student is to abstain from pursuing that path (r = .42).

Theme 2: Are Young Women Discouraged from Living Independently?

◉ Gender Differences in the Tendency to Avoid Relocating to Tokyo for University Education◉

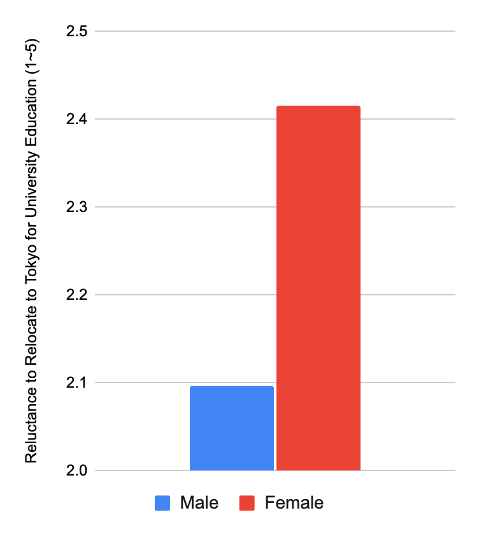

When examining those residing beyond the Greater Tokyo region, a distinct gender difference emerges regarding the inclination to relocate to Tokyo for university education. Specifically, girls, in contrast to boys, exhibit a greater reluctance to embark upon this transition [significant positive relationship (p < .05)]. Also as mentioned later, parents also exhibit a stronger preference for their daughters to pursue universities in proximity to the familial residence, as opposed to their sons [significant positive relationship (p < .05)]. Furthermore, while girls often attribute their hesitation to relocate to Tokyo to specific factors like "security concerns and financial constraints," boys frequently offer non-specific explanations such as "No particular reason" and "Preferring to remain in my hometown."

Figure 3: The average degree of “reluctance to relocate to Tokyo for university education” of male and female students./font>

◉ Parental Influence ◉

Similar to the observed influence in the case of "ronin," a discernible correlation arises between parents' preferences for universities located near their family's home and the propensity to resist relocating to Tokyo (r = .32). Hence, it can be inferred that the strong desire of parents for their daughters to commute from home is corelated with the hesitancy exhibited by girls towards pursuing a Tokyo- based educational.

◉ "Degree of Reluctance to Relocate to Tokyo" and "Percentage of Students Intending to Apply to the University of Tokyo" ◉

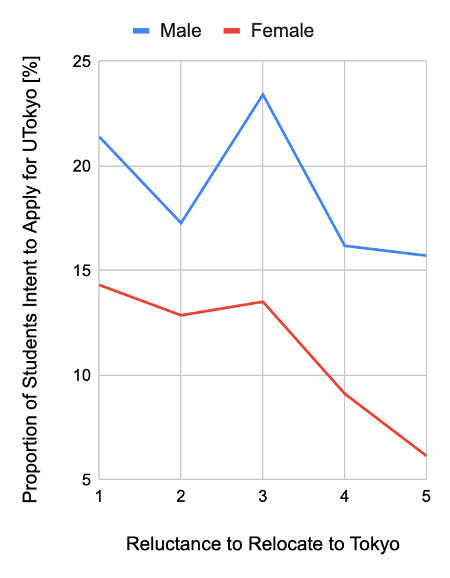

Exploring the dynamic between the "degree of reluctance to relocate to Tokyo" and the "percentage of students intending to apply to the University of Tokyo," a nuanced trend comes to light. Among women, a slight negative relationship is evident, implying that heightened reluctance to move to Tokyo coincides with a diminished inclination to apply to the University of Tokyo. The result for boys is less conclusive. This distinctive inclination appears to be characteristic primarily of girls.

Figure 4: The relationship between “reluctance to relocate to Tokyo for university education” and the proportion of students who has the intention to apply for the University of Tokyo.

Theme 3. Do Girls Have Greater Tendency to Place "Professional Certifications" ?

◉ Tendency to Place Importance on "Professional Certifications" ◉

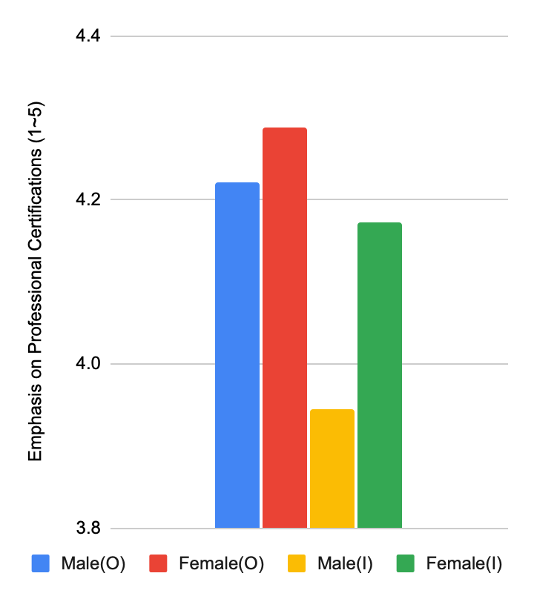

Nationally, a distinct gender disparity emerges, with female students exhibiting a higher inclination toward valuing careers with "professional certification" (such as physicians and pharmacists) compared to male students (p < .05). Moreover, this tendency is also pronounced among respondents residing outside the Greater Tokyo region, as opposed to their counterparts within the metropolitan area (p < .05).

It can be inferred that the heightened emphasis placed by women on certified professions stems from a pragmatic approach to addressing potential career interruptions arising from marriage and child-rearing responsibilities. This trend is even more pronounced in areas beyond Tokyo, possibly attributed to the visible presence of certification-based career models which significantly influence career choices in these regions.

Figure 5: The average degree of “emphasis on professional certifications” of male and female students inside and outside the Greater Tokyo area. (O) and (I) in the legend stand for “outside the Greater Tokyo area”, “inside the Greater Tokyo area”, respectively.

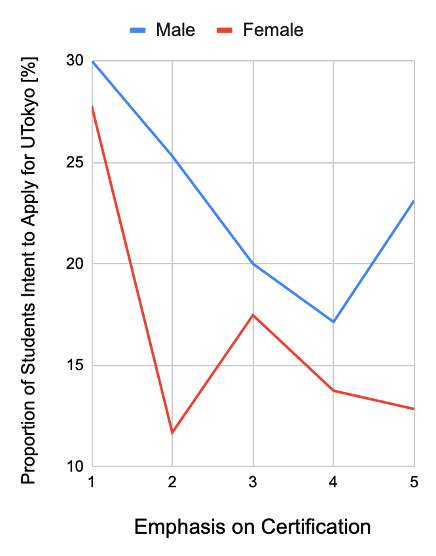

◉ Correlation between "Emphasis on Certification" and "Aspiration/Intention to Apply to University of Tokyo" ◉

Our analysis did not yield conclusive evidence to establish a distinct inverse relationship between the "tendency to emphasize certification" and the "degree of aspiration/intention to attend the University of Tokyo" for both male and female students.

It should be noted that only a very small proportion of the respondents placed low emphasis on certification among both genders. Consequently, the results were considerably influenced and potentially skewed by individual variations in responses concerning the “level of aspiration for University of Tokyo attendance”.

Figure 6: The relationship between “emphasis on professional certification” and the proportion of students who has the intention to apply for the University of Tokyo.

Theme 4. Do Girls Have Tendency to Underestimate their Academic Capability?

◉ Self-Evaluation of Personal Academic Aptitude ◉

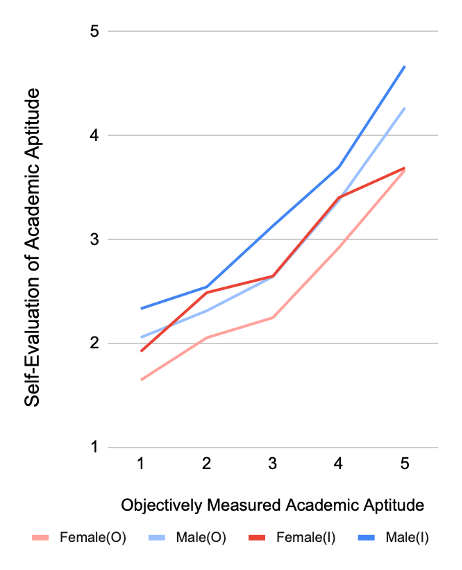

Across the nation, a notable discrepancy surfaces as girls exhibit a diminished level of "self-evaluation concerning their academic aptitude" compared to their male counterparts, particularly when their "objectively measured academic aptitude" is taken into consideration. In essence, girls tend to underestimate their own academic capabilities (p < .001).

Figure 7: The relationship between “objectively measured academic aptitude” and “self-evaluation of academic aptitude”.

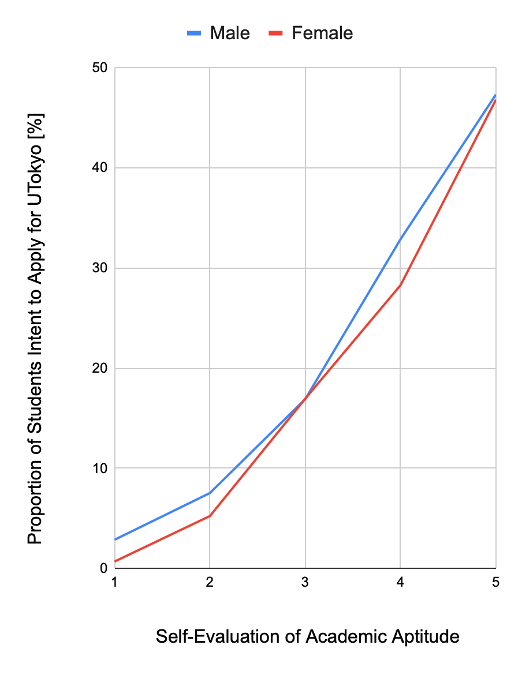

◉ Relationship between "Self-Evaluation of Academic Aptitude" and "Intent to Apply for the University of Tokyo" ◉

A conspicuous and positive correlation emerges between one's "self-evaluation of academic aptitude" and "intention to seek admission to the University of Tokyo," observed consistently among both male and female students. Consequently, it is possible that the limited self-assurance exhibited by female students regarding their academic competence significantly contributes to the limited representation of females at the University of Tokyo." (Refer to Footnote 2)

Self-evaluation is higher for both genders in the Greater Tokyo area than outside the area. This is probably because these respondents have a more realistic awareness of “what is necessary to pass the UTokyo entrance exam” by personally knowing those who have passed the exam.

Figure 8: The relationship between “self-evaluation of academic aptitude” and the proportion of students who has the intention to apply for the University of Tokyo.

Footnote 2: "Objective level of academic ability" was measured by combining the responses to two questions: "What do you think your current academic rank is among your classmates?" and "In your view, how many of your classmates are capable of gaining admission to UTokyo?" The respondent’s self-evaluation of the ability to pass the UTokyo entrance exam is measured by the question, "Assuming that you are interested in applying to UTokyo, do you think you will succeed if you study hard?"

Theme 5: Do Girls Tend to Place Less Importance on Their Educational Accomplishments (Gakureki) ?

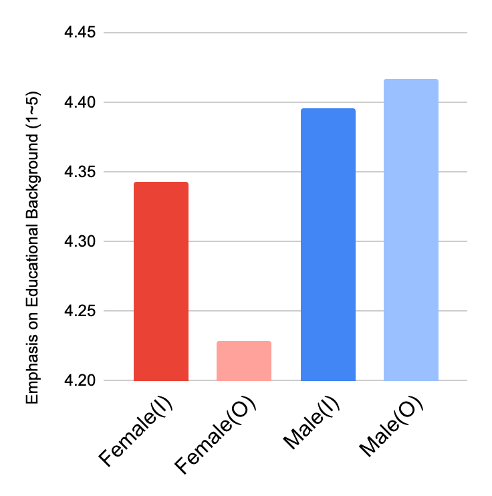

◉ Emphasis on Educational Accomplishments (“Gakureki”) ◉

The survey has found that, outside the Greater Tokyo area, compared to boys, girls tend to attach less importance to enrolling in high-ranking universities for their future (p < .001). On the other hand, no gender difference was observed among respondents from the Greater Tokyo area regarding this question.

However, since there was no difference in the response of boys in the Greater Tokyo area and the rest, it stands out that, comparatively speaking, girls outside the Metropolitan area, in particular, do not place much importance on the ranking of the university.

Translators’ Note: “Gakureki” is commonly defined as “the history of schooling received by an individual” which indicates the quality and amount of education he/she has attained.

Figure 9: The relationship between “self-evaluation of academic aptitude” and the proportion of students who has the intention to apply for the University of Tokyo.

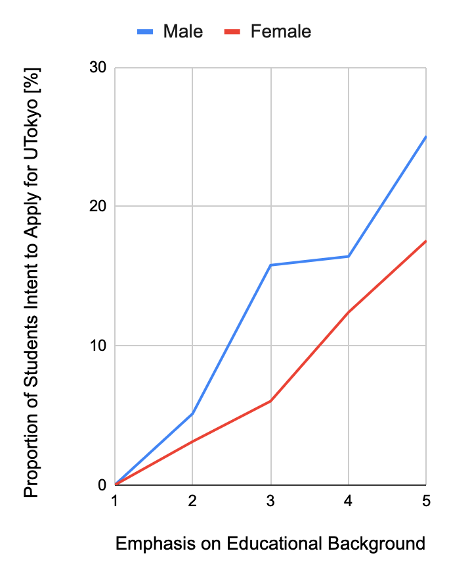

◉ "Tendency to Emphasize Educational Background" and "Aspiration to Attend the University of Tokyo" ◉

We found a positive relationship between "the tendency to emphasize the ranking of the university (that is, emphasis on “gakureki”)" and "aspiration to attend the University of Tokyo" for both men and women. Therefore, it can be said that the tendency for girls outside the Greater Tokyo area to place less emphasis on “gakureki” has had a considerable impact on their aspirations for enrollment at the University of Tokyo.

Figure 10: The relationship between “emphasis on educational background” and the proportion of students who has the intention to apply for the University of Tokyo.

◉ Influence of Parents/Guardians ◉

Among girls, the higher the preference of their parents for them to attend a high- ranking university, the greater emphasis they place on the ranking of the university they aspire to. (Greater Tokyo area: r = .21; Rest: r = .27) Also, outside the Greater Tokyo region, parents expect less from daughters than sons regarding enrollment in a high-ranking university (p < .05). Therefore, limited parental expectations may be a factor in the tendency of girls outside the Greater Tokyo area to not emphasize their educational background (“gakureki”).

Message from Polaris (UT) and Summary:

From the results of this survey, a significant conclusion has emerged: the propensity of girls to underestimate their academic abilities is closely intertwined with the disproportionately low representation of female students at the University of Tokyo.

Furthermore, several key factors have been identified as contributors to this phenomenon. These include the inclination of non-metropolitan girls to downplay their educational backgrounds ("gakureki"), the general female aversion to taking a "ronin" gap year for exam preparation, and the preference for avoiding residence in Tokyo. These factors collectively exert a noteworthy influence on the gender imbalance.

Conversely, the study did not yield substantial evidence indicating that the inclination of women to emphasize the significance of "professional certification" directly correlates with a diminished aspiration to attend the University of Tokyo. However, it is noteworthy that a prevalent sentiment suggests that highly capable female students from non-metropolitan regions often opt for regional medical schools over the University of Tokyo. Given the concurrent emphasis on "professional certification" among women, it is plausible that this attitude may have a connection to the underrepresentation of females at our university. To validate this hypothesis, further exploration is warranted.

At Polaris (UT), we are committed to leveraging the insights gained from this study to enhance our initiatives. Our aim is to provide more effective support for young women in junior and senior high schools as they navigate their career choices. Through a combination of events and social media engagement (SNS), we aspire to impart our own experiences from high school, entrance exam preparation, and university life. We believe that these endeavors will foster heightened motivation and self-assurance among female students in these crucial academic stages.

Within the University of Tokyo community, a multitude of women have encountered challenges such as "ronin" periods or relocating from non-metropolitan areas to independently reside in Tokyo. I am personally an example of such a background.

If this message resonates with your interests, we invite you to explore the Polaris (UT) website and connect with us through our social media channels (SNS). Additionally, we extend an invitation to join us at our upcoming events. Our team is eagerly anticipating the opportunity to engage in meaningful conversations with each of you.

Makoto Tanaka,

President

Polaris (UT) (at University of Tokyo)

Translators’ Notes:

● The Greater Tokyo Area in this report consists of the areas of Tokyo, Saitama,

Chiba, and Kanagawa.

● The Japanese version includes several graphs, which are currently being

translated.

Translators:

Masako Osako, PhD (Director, UTokyo Alumnae Association of America [ Satsuki-kai

America])

Naiara Y. Osako (Student majoring in economics and pollical science, University of

Edinburgh)

End